monografia Testo Italiano/Inglese offerta speciale : € 50,00 + spese postali |

Breve viaggio nella pittura di Gerico dal 1968 al 2008

di FAUSTO LAZZARI

La sua identità si costruisce su valori formali rigorosi e scientifici, oltre che su una tecnica acquisita con caparbia meticolosità, e si manifesta attraverso una lunga narrazione di contenuti pittorici, frutto di rivisitazioni delle ricchezze culturali del cosmo umano.

La sua grandezza si palesa nella quotidiana ricerca, fatta di piccoli passi nell’incessante percorso offerto dalle curiosità proposte dalla vita stessa.

La sua realtà si racconta nel segno, continuamente assetato di conoscenza.

La sua sensibilità si legge pagina dopo pagina, dipinto dopo dipinto, nella strutturazione grafica e pittorica del pensiero.

E, nonostante tutte queste apparenti certezze, non avrebbe senso tentare di definire univocamente l’appassionante percorso artistico di Gerico.

Quando si viaggia sulle vie della ricerca è ammessa solo qualche sosta ristoratrice, perché il viaggio tende all’infinito.

Lui, giustamente, li chiama anni sabbatici; sono più o meno lunghe pause tra un risultato acquisito e l’incognita di un nuovo sentiero da percorrere, con lo zaino riempito di strumenti di lavoro: pennelli, acrilici, testi letterari, insieme al cibo più nutriente che esista: cuore e mente che dialogano tra passato, presente e futuro.

Tutto ciò sempre con i piedi per terra, e non a caso, lasciando impronte indelebili e luminose, ampiamente testimoniate con precisione e dovizia sequenziale in questo catalogo, curato dall’autore stesso. Non è facile definire Gerico e la sua opera e non è neppure corretto costringerlo in un determinato movimento artistico piuttosto che un altro.

Gericoè un pittore completo nel vero senso storico della parola; non ama essere definito artista.

Questo termine lo ha spesso disturbato, anche per quella necessità di precisione che lo contraddistingue, al punto da indagarne l’etimo e la sua valenza

Il risultato gli ha dato ragione; un concetto troppo vago e astratto rispetto al suo pragmatismo operativo.

Preferisce quindi l’etichetta di pittore, di “artigiano dell’arte”: figura più legata alla manualità del fare, non disgiunta ovviamente da una consapevole capacità di argomentare il dipinto, proprio attraverso le abilità acquisite e una innata predisposizione.

La storia dell’arte gli viene incontro accogliendolo nella schiera di

coloro che hanno imparato le tecniche di questo mestiere per poterle applicare ad una personalenarrazione figurativa.

In pratica, si torna al concetto della fotografia, quando un paio di secoli fa ha reinventato la descrizione del vero, costringendo i pittori, da subito perdenti nel confronto con essa, a trovare nuove soluzioni rappresentative.

La sfida vera è stata proprio quella di continuare ad usare gli stessi materiali, confrontandosi con le stesse realtà, mantenendo lo stesso ruolo, incanalando abilità e pensiero in nuove visioni ed immagini; ciò che la fotografia non potrebbe mai documentare.

Alla luce di queste considerazioni, proviamo a seguire questo quarantennale percorso, ricco di contenuti e di argomenti, articolato in periodi tematici differenti, legati insieme sempre e comunque almeno da due motivi: il primo, più concreto, di carattere squisitamente tecnico, che consiste nella manualità dell’artigiano- pittore; Ilsecondo, più concettuale, costruito in modo complesso e completo sulla creatività narrativa della rappresentazione, in altre parole, relativo al desideriodi raffigurazione di un pensiero.

L’amalgama tra l’abilità tecnica e una vulcanica esposizione di pensieri conduce direttamente nell’immenso cosmo dipinto da Gerico, una vera e propria opera pittorica che tende all’universale, degna di essere individuata come un’ampia “letteratura visiva.

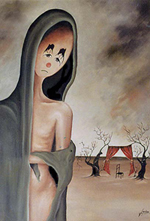

Il primo “tempo” è squisitamente pittorico e particolarmente legato alla tecnica, alla conoscenza e alla sperimentazione dei materiali, all’uso dei colori, prima gli oli poi le tecniche miste. Dal1968 al 1971 il pittore, da autodidatta, si mette alla prova, con curiosità ed entusiasmo, lavorando con tenace assiduità per imparare il “mestiere”,

per entrare in possesso dei segreti di un linguaggio che non può fare a meno di regole.

Tutto ciò potrebbe essere applicato più facilmente a quello che la tradizione e le accademie insegnano. Invece no. Gerico, immediatamente e senza pretese genialoidi, individua un pensiero da rappresentare, cominciando così a raccontare le sue giovanili idee intrise di spunti psicologici, in un costante intreccio tra conscio e inconscio.

(1) (1)

|

Si evidenzia da subito la volontà prolifica del pittore

entusiasta di trovare soluzioni capaci di narrare e di emozionare al tempo stesso, pur conla consapevolezza di costruire equilibri formali, importanti per quello che

verrà definito il “Fantasma estetico”, intendendo appunto questo primo periodo di lavoro.

Il sostantivo “fantasma”può essere riferito a tutto ciò che Gerico cerca di raccontare nei dipinti di quegli anni, sempre e comunque abbondanti di spunti lirici costruiti dentro scenari surreali. L’aggettivo “estetico” appare più consono alla struttura della scena, tesa ad un equilibrio formale piuttosto complesso dentro una fitta ragnatela di segni e colori.

In questo primo approccio alla pittura esiste già la possibilità di individuare un momento di arricchimento stilistico. Ciò è facilmente visibile in opere come “Il Ponte” (fig.3) e “L’appuntamento” (fig.4) del 1970, per caratterizzarsi a partire dal 1971, quando il supporto,

(3) (3)

|

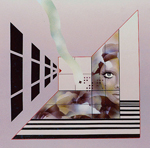

Anche la dimensione dello spazio, che inizialmente tende alla profondità dell’orizzonte aperto verso paesaggi ampi, si manifesta invece dentro contenitori definiti, più facilmente riconducibili ad una messa in scena, dentro cornici e palcoscenici, nelle linee precise della figura geometrica del quadrato.

“Il pensiero” (1971-fig.5), ad esempio, si libera di molti elmenti descrittivi e diventa una interferenza luminosa, un segmento obliquo dentro la costruzione semplice delle linee rette di un quadrato che ne contiene altri nove.

Dopo questo “primo periodo”, dedicato soprattutto allo studio, i cui contenuti non sono comunque mai usuali, perché è sempre il pensiero che cerca i modi per poterli esprimere, Gerico inizia a strutturare un panorama discorsivo ed eloquente sul rapporto “natura - uomo - macchina”.

(5) (5)

|

La contemporaneità propone “sentimenti” meccanografici, pre tecnologici.

Si tratta, appunto, dei prodromi della tecnologia, quelli delle schede perforate e di una nuova automazione, futura

genitrice di schermi al plasma e micro processori in byte.

Una realtà dinamica e affascinante nella sua bellezza estetica, quanto crudele nell’appariscente servizio reso all’umanità.

In tempi veloci quanto drammaticamente vissuti si realizzano tristi processi di assorbimento, in cui il prodotto ha sempre una marcia in più rispetto al suo produttore.

Sono spesso i “Totem” (1972- fig.6), con oltre cinquanta variazioni sul tema, a caratterizzare la vitalità di questo dramma: grandi strutture meccaniche che si ergono a sbandierare il loro potere

a stelle e strisce, con la brillantezza di una turgida virilità che non lascerà spazi di sana sopravvivenza ai suoi “geniali” costruttori. La proiezione umana dell’entusiasmo produttivo della macchina, che tende a realizzare risultati sempre più performanti, insieme alla sua apparente bellezza, costringono sia l’uomo che l’ambiente a subire ogni dinamica di questo scontro “amoreodio”.

L’uomo stesso è costretto ad una nuova identità, frutto del condizionamento produttivo di un sistema dominato dalla macchina. Ecco quindi che l’autore introduce nuovi elementi simbolici,

conseguenza di un percorso che cerca e trova intelligenti soluzioni estetiche, per raccontare

questa confiittualità, che l’economia tende a leggere superficialmente come fenomeno di benessere.

(7) (7)

|

“Ho sempre lavorato cercando simbologie da rappresentare - dice lo stesso Gerico - e ciò che

dipingo è simbolico, per quanto continui a mantenere una rispettosa confidenza con il mestiere

del pittore e con i canoni storici della pittura”.

Contemporaneamente l’autore introduce un ulteriore elemento simbolico: il barattolo.

La sua geometria cilindrica è essenziale e diventa costruzione dinamica nella ripetitività dell’oggetto, in una accumulazione facilmente riconducibile alla produzione di massa.

Ma il barattolo, per Gerico, è anche un’immagine simbolo, intesa come unità di misura della libertà. Una libertà concreta e spietata, che si avvale di numeri e di quantità: tanti barattoli, tanto potere e questo potere equivale ad una precisa possibilità di consumo.

Consumare cosa? Gli stessi barattoli, simbolo e sintomo di una impietosa omologazione (“Predisposizionamento al consumo n° 1”, 1978-fig.8).

(9) (9) |

È la negazione della coscienza critica e della consapevolezza

dell’individuo: il mezzo televisivo, mediante la potente arma di una capillare diffusione della trasmissione, fonde la verità con la finzione e un tragico evento di sangue, ad esempio, perde la sua reale connotazione, confusa tra un telegiornale, uno spot pubblicitario e un telefilm. (Video n. 2 del 1977 - fig.9)

I barattoli, che Gerico distribuisce sulla tela da uno schermo

all’altro, funzionano da unità di misura del consumo, annientando la capacità di lettura intelligente e uniformando il criterio intellettivo a quello computerizzato.

Il livello di sensibilità comune della società e le sue relative

argomentazioni etiche si abbassano sempre più e, come appare nei dipinti di questo periodo dominato appunto dalla macchina, si definisce l’ingabbiamento conservativo: un automatismo che riguarda indifferentemente ogni forma sia di produzione che di consumo.

Produzione di barattoli, come contenitori di beni da consumare; produzione di vicende umane, come soluzioni dell’immaginario collettivo:entrambi, e non casualmente, un’identica modalità di “alimentazione”.

Il tutto all’insegna della costruzione guidata di una incapacità di pensare autonomamente a favore del “pensiero” già confezionato, di facile acquisto e di ancor più facile consumo.

Quando, dopo la completa “consumazione”, resta solo il drogato desiderio della consumazione dice Gerico- andare incontrollabilmente “oltre”, (da 1 si passa a 2, poi a 3, a 4,5,6,....e via così

all’infinito fino all’inevitabile “Tilt”), vi è molta probabilità che il destino umano sia scritto.

(Tilt- 1977-fig.10).

Punto e a capo.

Gli anni Ottanta, iniziano con una pausa di lavoro.

Un anno sabbatico è spesso fondamentale per continuare un percorso fatto di impegnativi approcci alla realtà e ragionate considerazioni sui valori che si possono esprimere con la pittura.

Nel 1981 il pensiero si struttura attorno ad una nuova opportunità di utilizzare la macchina; ma

questa volta con una valenza positiva e in un dialogo decisamente costruttivo tra uomo e nuove

tecnologie.

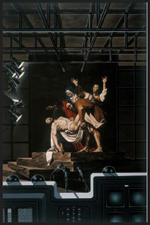

Nasce così quello che verrà definito il “Museo vivo”, un’originale ricostruzione di una felice e illuminata musealità che appartiene alla storia dell’arte.

Le opere di autori particolarmente amati da Gerico, quali David, Hayez, Vermeer, Jerome, Ingres, ma soprattutto Caravaggio, diventano i soggetti di una nuova lettura, più adatta ad una

contemporaneità contaminata dalla tecnologia.

I contenuti di famosi dipinti vengono messi in scena in una sorta di rivitalizzazione dell’asfittico

concetto di ambiente museale.

L’ambiente destinato a contenere tali importanti opere sarà appunto la scena, uno spazio precisamente definito e fisicamente contenuto in uno studio cinematografico, televisivo o più semplicemente fotografico, in una sorta di “steel life” della riproduzione.

Il lavoro si predispone, quindi, su due piani: il primo è relativo alla ricostruzione fedele dell’opera originaria, senza teorie citazioniste né forzati tentativi di rivisitazione; il secondo riguarda la messa in scena della stessa opera, alla luce di tutti quelli che possono essere i mezzi atti e necessari a creare una teatralità dell’evento.

Di conseguenza, Gerico si propone anche come regista e scenografo del dipinto che sceglie di

mettere in scena, proprio come fosse sul set di un film, pronto per la ripresa.

E lo fa ponendosi un passo dietro a tutte le attrezzature che servono per riprendere il “momento storico” della ricostruzione del dipinto.

Una ricostruzione sempre ricca di studi grafici e disegni di geometrie funzionali ad individuare l’angolazione visuale più adatta alla messa in scena tra tagli di luce,

In effetti le telecamere non hanno la funzione di riprendere il quadro, ma la loro presenza crea

una nuova realtà, più articolata e contaminata tra elementi classici e contemporanei curiosamente

mischiati insieme.

Ciò che è tipicamente museale diventa parte di una più complessa ricostruzione scenica.

Ponderata è ovviamente la scelta degli autori, a partire dal Caravaggio, che oltre alla loro grandezza si prestano più di altri ad una ulteriore teatralità sia visiva che pittorica.

“La sfida che più mi entusiasmava - spiega ancora Gerico in relazione all’esperienza di questo

“Museo vivo” - era data dalla possibilità di assimilare in un’unica situazione l’arte di questi

grandi maestri con i mezzi della riproducibilità odierni”.

I titoli di questi lavori, oltre a citare l’autore, sono sempre espressi dal sostantivo "performance”, ad indicare la ridefinizione dell’opera nella nuova identità scenica.

“La deposizione” , ad esempio, riscritta come“Caravaggio performance”(fig. 12) e datata 1982,

segna in maniera importante l’inizio di questo viaggio del pittore-regista, ma anche lo chiude

con lo stesso titolo nel 1991.(fig.13)

(12) (12)

|

Tra le due opere corre un decennio nel quale Gerico individua e realizza un enorme “Museo vivo”, attraversando la bellezza, la drammaticità e la complessità scenografica di questa pittura

La ricerca porta con sé un rischio concreto.

Quando succede di riuscire a trovare un risultato importante è ovvia la tentazione di arenarsi su di esso, trasformandolo in una soluzione definitiva.

Ciò che si ottiene diventa una formula gratificante, facilmente ripetibile.

Ma è un atteggiamento che il ricercatore vero rifiuta per indole e perché la sua ricerca non è altro che un filosofico viaggio dentro una continua e logorante sfida con sé stessi.

Anche il “Museo vivo” arriva, dunque, ad una logica conclusione.

Esaurite tutte le opportunità d’indagine all’interno di questa contaminazione tra le diverse modalità di mettere in scena l’opera d’arte, Gerico si ferma.

Un altro risultato è stato ottenuto e una sua ulteriore ripetizione non interessa all’autore, in cerca di nuovi stimoli creativi.

|

Il committente vuole essere raffigurato in uncerto modo e in un determinato contesto; queste richieste rappresentano uno stimolo importante che si pone due obiettivi: quello di gratificare chi viene immortalato e quello di soddisfare le esigenze creative dell’autore, le quali sottendono un adeguato impianto costruttivo ed eloquenti risvolti psicologici nell’identità di chi viene immortalato.

Così appaiono evidenti i valori comunicativi di certi ritratti, quali la suggestiva collocazione marinara di “Maurizio” (1988-fig.14), la raffinata eleganza di “Edy Guerrini” (1989-fig.15), la passionale immedesimazione della signora “Paola” (2007-fig.16), diretta interprete di “Leda” dalle “Metamorfosi di Ovidio”.

(15) (15)

|

in posa”.

“La teatralità del mettere in scena - spiega Gerico a tal proposito - mi ha portato a considerare il grande tema della natura morta.

Frutti e verdure sono le stesse da secoli, ma per me non si trattaperò di normali nature morte, perché esiste questo forte legame con la teatralità che mi stimola a mettere in posa della frutta per mostrarla in tutta la sua bellezza e arroganza”. (fig.17)

Si potrebbe parlare quindi di una ricerca dell’innaturalità della natura; un po’ come quando si sostiene che qualcosa è così bello da sembrare finto o, così finto da apparire vero.

In questa ambiguità tra finzione e realtà, ancora una volta la “messa in scena” diventa illuminante rispetto ai contenuti proposti con una sapiente e rigorosa pittura.

Senza dimenticare, oltretutto, che l’autore utilizza i colori acrilici con una personale tecnica capace di renderli caldi e pastosi come fossero oli.

Calore e freddezza si mescolano insieme, ricreando immagini calcolate nei loro equilibri, anche grazie ad un ingabbiamento costruito ad arte e realizzato tra fili tesi che s’incontrano nel dipinto per definire spazi e rifrangenze luminose.

Il senso della potenza vitale e la presunzione di perfezione di queste “nature in posa” viene ricomposto dal pittore attraverso altre sensazioni, che dichiarano dove sta il vero potere: compostezza, equilibrio e ingabbiamento, in una visualità teatrale di cui solo l’autore possiede

le chiavi interpretative.

Suggestioni sceniche di ambientazione irreale, in cui la luce dialoga prepotentemente con tutto ciò che si espone: in sintesi, questa è la sensazione visiva che caratterizza tale ulteriore teatralità dell’immagine realizzata da Gerico.

In un “clik” si può riassumere l’imponente sfida pittorica che Gerico decide di considerare a partire dal 1999, quando comincia un lungo viaggio nella letteratura dantesca.

È un percorso che, mantenendo una sua personale autonomia, egli affronta in compagnia di altri tre pittori: Edi Brancolini,Danilo Fusi e Impero Figiani, modenese il primo e toscani gli altri due.

Li unisce il desiderio di trovare forme espressive che attraverso la pittura riescano, senza nessuna velleità illustrativa, a confrontarsi nell’interpretazione del testo letterario.

Non un testo letterario qualsiasi, ma uno dei più alti della storia della letteratura: la “Divina Commedia” di Dante Alighieri.

Ancorauna volta, come nell’approccio al rapporto “uomo- macchina” dei primi anni Settanta, l’autore individua una scelta di contenuti in anticipo rispetto agli interessi culturali del tempo.

Un “clik”, si diceva, che contiene simbolicamente questo complesso ed originale itinerario.

Il clik della macchina digitale: la velocità di un attimo per ottenere un risultato concluso immediatamente in milioni di pixel, il rumore di un polpastrello sul tasto “invio” della tastiera del pc.

Un mix tutto contemporaneo per tentare di utilizzare al meglio le tecnologie più avanzate in funzione di un pensiero classico quanto universale.

“Navigazione ultima” è il titolo di questa operazione, condivisa da Gerico con i suoi compagni

di “viaggio” e testimoniata, oltre che dalle opere e dagli studi realizzati, da una mostra didattica

itinerante con la presenza di oltre 30.000 visitatori e da un importante catalogo a cura di Giorgio

Segato (editore La Litografica, Carpi, 2000), il cui sottotitolo recita: “Quattro itinerari dell’immagine dentro l’uomo di Dante”.

( Questi itinerari “convergenti” non sono frutto di improvvisazione; d’altra parte la pittura di Gerico è tutt’altro che improvvisata e superficiale.

Già nel 1997, sempre per i caratteri della stessa casa editrice viene pubblicato il catalogo “4 pittori dello sguardo cristallino” a cura di Giorgio di Genova, che cementa il sodalizio artistico di Brancolini, Fusi, Gerico e Nigiani, i quali condividono una comune idea del linguaggio pittorico e che vivono pienamente la modernità nel rispetto della tradizione).

“In questo mio lavoro attorno al singolo episodio - precisa Gerico - si sviluppa una figurazione che lega tutte le opere in un unico codice di lettura.

Gerico è sempre particolarmente attento a rapportarsi con il reale che avanza; essendo il pc un

quotidiano elemento della contemporaneità esso non può non apparire nella sua narrazione pittorica, ma in questo caso la macchina è anche rappresentativa del sapere del sommo poeta, capace di ricostruire nella sua grande opera tutte le conoscenze di un’epoca, mai disgiunte comunque dall’appagante apprendimento dei classici.

“Parto sempre da uno spazio nero incolore, come internet che non ti prospetta alcuna idea di colore - aggiunge Gerico - e questa idea potrebbe essere simbolica del cosmo, del tutto e del nulla, in un pulviscolo dentro cui esiste appunto il tutto e il nulla.

Questo pulviscolo, da cui parte tutto, è la memoria collettiva spazio - temporale dell’umanità.

Ogni punto, per quanto infinitamente minuscolo, contiene una storia eternamente fiuttuante

e sospesa.

Con la dinamica operativa del pc e i versi specici di alcune terzine di Dante, individuo uno di questi minuscoli punti e lo porto in primo piano, in modo che possa offrire una dettagliata

visibilità della circostanza considerata”.

Prendiamo, ad esempio, un episodio eclatante e proviamo a raccontarlo per capire il meccanismo

della tecnica rappresentativa.

(19) (19)

|

La navigazione in internet parte dal primo piano dove campeggia una tastiera di computer, simbolicamente utilizzabile per collegarsi con uno della miriade di piccoli punti nella parte alta del quadro.

Il contatto si visualizza in un cono di luce che parte da quel lontano universo con una serie di cerchi concentrici sempre più grandi, l’ultimo dei quali mette a fuoco al centro dell’opera l’episodio analizzato.

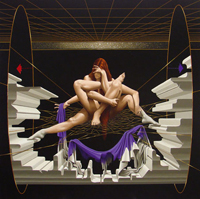

In uno “zoom” Paolo e Francesca, abbracciati, sono due anime senza corpo, due fantomatiche figure prive d’identità, drammaticamente avvinte l’una all’altra e lievemente posate sul grande libro, che è l’alibi del loro scandalo d’amore.

Appena alle loro spalle la grigia sensualità dei corpi tra i vapori fatui, nel ricordo del peccato

lussurioso.

Alla loro destra e più in basso sosta Dante, anch’egli freddamente paludato della stessa veste

incolore.

Nell’incontro figurano anche cinque terzine del Canto V dell’Inferno, letterali testimoni di uno dei dialoghi più conosciuti e intensi dell’intera Commedia.

Dal buio che tutto comprende, appoggiata alla tastiera, nell’angolo opposto all’universo stellato,

si contrappone una mela rubiconda e sontuosa che fa bella mostra di sé, frutto di quel peccato,

ma anche elemento reale ed invasivo, capace di trasmettere un calore estraniante nella complessità tenebrosa e fredda del dipinto.

Questo tipo di analisi si affida comunque ad un approccio immediato e superficiale, che non trova facili parole perché il lavoro pittorico di Gerico merita ben altra attenzione nel gioco delle possibilità visive e nella costruzione delle simbologie iconografiche.

Alla luce di questa originale e preziosa esperienza di “navigazione” nella Commedia dantesca, che contiene in sé anche nuovi valori didattici nel rapporto tra il testo letterario e l’iconografia che da sempre lo accompagna, il percorso di figurazione dell’opera di Dante è destinato a compiere ulteriori passi avanti.

Corrado Gizzi, direttore della Casa di Dante in Abruzzo, già autore di molte e importanti iniziative culturali finalizzate a mantenere costante e illuminata la figura del sommo poeta, propone al gruppo dei quattro pittori (Brancolini, Fusi, Gerico e Nigiani) una sfida che nessuno fino ad oggi ha mai affrontato: l’interpretazione pittorica della “Vita Nuova”.

“L’invito a proseguire questo meraviglioso viaggio - racconta Gerico - è stato sicuramente un

ulteriore stimolo di ricerca. In questo caso, però l’iconografia era scarsissima, quasi inesistente

e leggendo l’opera ci si rende conto anche del perché nessuno mai abbia cercato di interpretarla

in immagini”.

Nell’autunno del 2003, dopo tanto lavoro e con altrettanto entusiasmo, al castello di Torre de’ Passeri a Pescara, vengono presentati il volume e la mostra dedicati appunto alla “Vita Nuova”

interpretata dai quattro autori.

Gerico mantiene l’impostazione strutturale dei precedenti dipinti, individuando ancora una forte

componente emotiva nell’intreccio della rappresentazione: un fondo di nubi cupe e burrascose,

da cui emerge un tema centrale contenuto in una sintesi di geometrie semplificate e un primo piano sulla cui base, al posto della tastiera del computer, ci sono: un libello aperto su pagine intonse, un calamaio con inchiostro e penna a scandire il tempo e una danzatrice, diretta interprete della parole e dei pensieri dedicati da Dante ad una Beatrice angelicata.(la morte di Beatrice-cm.80x90 - fig.20)

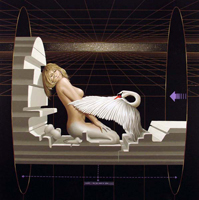

Lo stesso Corrado Gizzi, tre anni dopo, nel 2006, firma il volume “Dante e Ovidio” con lo stesso criterio del precedente lavoro, per rappresentare, attraverso il collaudato poker di firme, le fonti ovidiane presenti nella Divina Commedia.

Anche questo progetto non ha particolari precedenti, per cui, ancora una volta, si rende necessario uno studio metodico e approfondito dei testi nell’intenzione di una creatività originale quanto pertinente.

Gerico, per questa commissione, cerca una nuova chiave di lettura, per andare oltre le soluzioni

adottate nelle precedenti interpretazioni dantesche, confermandone però l’impostazione grafica. “Mantenendo fermo il concetto di memoria collettiva spazio - temporale, - precisa ancora Gerico - dentro questa dimensione ho creato due aperture, due tagli prospettici circolari nei quali

scorre una colonna che diventa un teatro scavato in cui si manifestano forme scultoree che prendono vita dal marmo stesso, in una sorta di realtà che nasce dal mito”.

È proprio così che la dura pietra concede spazio alla vita con effetti pittorici che appaiono magici.

Emblematiche, a questo proposito, le mitiche figure di “Aracne”(2006-cm.80x80-fig.21) con i

suoi otto arti intrecciati nell’armoniosa femminilità del corpo e di “Leda” (2006-80x100-fig.22) la cui sensualità si compone “sotto le ali del cigno”, citando un passo delle “Metamorfosi” di Ovidio e contemporaneamente i versi 97 e 98 del XXVII Canto del Paradiso: “E la virtù che lo sguardo m’indulse, / nel bel nido di Leda mi divelse,”.

(22) (22)

|

di Gerico, soprattutto in queste ultime sfide culturali, con le grafiti su tavole gessate che, oltre ad avere il valore dello studio, narrano di geniali operazioni, esaustive nella forma ed efficaci nella suggestione dei contenuti. (Argocm. 60x80). (Dafne-cm.50x60).

Non è certo facile caratterizzare la figura e l’opera di Gerico, anche perché non è autore riconducibile ad una definizione contenibile in uno schema univoco.

La sua curiosità e le sue intenzioni lo hanno sempre messo di fronte ad una realtà vivacemente ricca di drammaticità umana in un divenire culturale fragile e di graffianti interrogativi; la sua sensibilità e il suo pensiero lo hanno proiettato lungo sentieri tracciati nell’immenso universo che fiuttua nella ricerca.

(23) (23)

|

Questa caratterizzazione - sostiene giustamente Gerico - non limita mai l’impulso di rinnovamento perché, “sebbene nessun marinaio, navigando, abbia mai ridotto la sua distanza dall’orizzonte, navigare resta una vocazione indomabile e guadagnare nuovi orizzonti è l’emozione più disperatamente vitale per ogni essere umano”.*

Crema, febbraio 2008

Fausto Lazzari

* Vittorio Sermonti (...)

monograph Text Italian//English special offer: € 50,00 + postal tarrif. |

A brief journey into Gerico’s work from 1968 to 2008

by FAUSTO LAZZARI

Its identity is based on rigorous and scientific formal values, as well as on a technique acquired with a stubborn meticulousness showing itself through a long narration of pictorial contents deriving from the revisitation of the cultural patrimonyof the human cosmos.

Its greatness becomes evident in the daily research, made up of minute steps in the unceasing route offered by the curiosities of life itself.

Its reality is told through the sign, continuously thirsty for knowledge.

Its sensitivity is read page after page, painting after painting, in the graphic and pictorial structurization of thought.

And despite all these apparent certainties, it wouldn’t make sense to try

to dene univocally the fascinating artistic path made by Gerico.

When you travel on research ways, only few refreshing stops are allowed

because the journey gets eternal. He calls these stops “sabbatical year” in the right way: it’s more or less long pauses between a result acquired

and the uncertainty of a new path to follow, with the backpack filled with all the necessary work tools: paintbrushes, acrylic colours, literary

texts as well as the most highly nutritious food: heart and mind having a dialogue between past, present and future.

The whole occurs with a down-to-earth attitude, and, as a matter of fact, indelible and luminous footprints are left on the ground, widely witnessed with precision andsequential abundance in the present catalogue, edited by the author himself.

It is not easy to define Gerico and his work; yet, it isn’t correct toconstrain him in a specific artisticmovement rather than another one. Gerico is a complete painter in the real historical sense of the term; he does not love to be defined as an artist.

This term has often annoyed him, also because of that need of precision typical of him, which always leads him to examine in details the etymon and its value.

So he prefers the “painter” or “artisan” label, which are figures more related

to the manual ability, obviously not detached from the aware ability to argue a painting through the skills acquired and thanks to an inborn bent.

The History of Art approaches him welcoming him in the group of those who have learnt the techniques of this trade in order to apply them to a personal figurative narration.

It is practically like going back to the concept of photography, when a couple of centuries ago it reinvented the description of what is true, obliging the painters, considered as losers compared to it, to find new representation solutions.

The real challenge was the act of continuing to use the same materials,confronting themselves with the same realities, maintaining the same role, directing abilities and thoughts into new visions and images, which is exactly what photography could never be able to document.

In the light of these considerations, let’s try to follow this 40-year-long route, rich in contents and topics, articulated in different thematic periods, yet always linked together for two main seasons. The first reason, which is more concrete and exquisitely technical, is the artisan’s -painter’s- manual ability.

The second one is more conceptual, built up in a complex and complete way on the narrative creativity of representation, in other words, related to the desire of depicting a thought.

The mixture between technical ability and a volcanic exposition of thoughts directly leads into the boundless cosmos painted by Gerico, a real pictorial work which becomes universal, worthyof being defined as a wide “visual literature”.

The first “part” is exquisitely pictorial and particularly related to technique, the knowledge and experimentation of materials, the use of colours, first oils and later mixed techniques. From 1968 to 1971 the painter, a self-taught man, wants to test himself with curiosity and enthusiasm, working with tenacious diligence to learn the“trade”, to possess the secrets of a language which can’t avoid rules.

All this could be applied more easily to anything tradition and academies teach. However, it can’t.Gerico immediately envies -without any genius pretension- a thought to represent, thus starting to tell about his young ideas rich in psychological hints in a constant weaving of conscious and unconscious.

.......................(2) .......................(2) |

highlighting not only the curiosity of experimenting,but also the complex relationship of the author with the world, society, some avantgardes of the early 20th century, and especially

with the desire to directly enter the endless twists of the human psyche in order to try to tell some of them on the canvas.

You can immediately feel the prolific will of the painter who is enthusiastic about finding solutions able to tell and raise emotions at the same time, aware of building formal balances which are important for what will be defined as the“Aesthetical Ghost”, term used to entitle this first period of work.

The noun “ghost” can be referred to anything Gerico tries to tell in the paintings of those years, always rich in lyrical hints framed in surreal scenarios.

The adjective “aesthetic”appears to be more in accordance with the structure of the scene, directed to a rather complex formal equilibrium inside a close web of signs and colours.

In this first approach to painting, it is already possible to identify a moment of stylistic enrichment. This is clearly visible in works such a“The Bridge”(fig.3) and “The appointment” (fig.4) of 1970, and it will appear more characterized starting from 1971, when the support, the cotton canvas, starts containing in itself a narrative structure which gets complete in complex and tidy relations of elements as well as in simple and numerous geometries containing objects and subjects which acquire a suggestive symbolic dimension.

........................(4) ........................(4) |

After this “first period”, especially dedicated to study, whose contents are never usual, because it is always the thought which looks for the ways to express them, Gerico starts structuring a conversational and meaningful panorama concerning the relationship “nature-man-machine”.

It’s 1972. With a certain cognitive anticipation in the ethic considerations on epochal themes,

the author focuses his attention onto the confiictual values where man and nature suffer from the

behavioural models of the machine, once more assumed as the warning sign of the post industrial modernity.

Contemporaneity proposes “mechanographic,pre-technological “feelings”, warning signs of

technology, like the pieced cards, and of a new automation, later generating plasma displays and byte microprocessors.

A dynamic and fascinating reality in its aesthetical beauty, cruel in the remarkable service offered to humankind.

In such quick and dramatically lived times sad absorption processes take place, in which the product is always a cut above its producer:The “Totems” (1972-fig. 6), with over fifty variations, characterize the vitality of this drama: big mechanic structures showing off their stars and stripes power, with the brightness of a turgid virility which will give no space of a healthy survival to its “ingenious” producers.

The human projection of the machine’s productive enthusiasm, which performing results,

So the author introduces new symbolic elements, which are the result of a path looking for and finding intelligent aesthetical solutions, which economics tends to read superficially as a phenomenon of wealth.

Here the author introduces anonymous and homologous masses of people looking like well forged and completely bandaged manikins, characterized by a cold “aluminium” effect (for example,“Video n. 3) of 1977-fig.7).

These devitalized human beings are constrained in sequential processes of pigeonholing, multiples of themselves within a process so dominated by machine that it even transforms the “human system” to its image and likeness.

“I have always worked looking for symbols to represent - says Gerico - and what I paint is symbolic, no matter how much I continue to maintain a respectful condence with the trade of painter and with the historical canons of painting”.

At the same time the author introduces a further symbolic element: the tin. Its cylinder geometry

is essential and becomes dynamic construction in the repetition of the object, in an accumulation

which is easily referable to mass production.

A concrete and merciful freedom, which avails itself of numbers and quantities: many tins, a lot

of power, and such a power equals a precise possibility of consumption. To consume What? The

tins themselves, symbol and symptom of a pitiless homologation (Predispositioning to consumption n.1), 1978-fig.8).

.......................(8) .......................(8) |

films. (Video n.2 of 1977 - fig. 9).

The tins, which Gerico distributes on the canvas from a screen to the other, work as units of measurement of consumption, annihilating the ability to read intelligently and adapting the intellectual criterion to the computer one.

The society’s level of common sensitivity and its relativ ethic argumentations get lowerand lower and,as shown in the

paintings of these years dominated by machine, the conservative entrapment is defined: an auto-matism touching any form of production and consumption indifferently. Production of tins, as containers of goods to consume; production of human events, as solutions

of collective imaginary: both have, and not randomly, an identical modality of “alimentation”.

And all this is marked by a construction which is guided by an incapability to think autonomously, in favour of the ready-made “thought”, easy to purchase and even easier to consume.

“When, after the complete “consumption”, - says Gerico - there is only the doped desire of consumption to go “beyond” without any control (from 1 to 2, then to 3, and 4,5,6… and so on endlessly until the inevitable “haywire”), there is a great probability that the human destiny is written (Tilt (Haywire)-1977-fig.10) .

Full stop and new paragraph.

|

In 1981 the thought structures itself around a new opportunity to use the machine: this time with a positive value and in a definitely constructive dialogue between man and new technologies.

This is the birth of what will be called the “LiveMuseum”, an original reconstruction of a happy

and illuminated museum belonging to the history of art.

The works of authors particularly loved by Gerico, such as David, Hayez, Vermeer, Jerome, Ingres, but especially Caravaggio, become the subjects of a new reading, more suitable to a new contemporaneity contaminated by technology.

The contents of famous paintings are staged in a sort of re-vitalization of the feeble concept of

museum environment.

The space bound to contain such important works is the scene itself, a space precisely defined and physically contained in a cinematographic, TV or photographic studio, in a sort of “steel life” of reproduction.

The work is therefore articulated on two layers: the first one concerns the faithful reconstruction

of the original work, without quotation theories and forced attempts of re-edition; the second one deals with the staging of the work itself, in the light of all the possible tools needed to create the theatricalism of the event.

So in the foreground are present shooting cameras, telecameras, light mixers, direction panels,

scaffoldings, tubular castle structures with screened headlights and spotlights; the essentiality

of set contexts suitable to amplify and highlight the suggestion of the work (David and Goliath

1982-fig.11).

.................................(11) .................................(11) |

A reconstruction always rich in graphic studies and geometric drawings to detect the most suitable visual angle-shot for the staging, among light cuts, volume dispositions and formal equilibriums.

In fact, telecameras are not supposed to shoot the painting, but their presence creates a new reality, more articulated and contaminated between classical and contemporary elements curiously mixed together.

What is typical of a museum becomes the part of a more complex set reconstruction.

The choice of the authors is very considered, starting from Caravaggio, offering, next to their

greatness, a further visual and pictorial theatricalism.

“The challenge which made me more and more enthusiastic - explains Gerico speaking about his experience with this “Live Museum” - was the possibility to assimilate in a single situation the art of these great masters with today’s reproducibility media”.

The titles of these works quote the author and express the noun “performance”, in order to

identify the re-definition of the work in the new stage identity. “The Deposition”, for example,

re-named “Caravaggio performance” (fig.12), dated 1982, marks the start of this journey, but

also closes it with the same title in 1991. (fig.13)

...............................(13) ...............................(13) |

proposes in the foreground a direction place,

some microphones and directionable spotlights to

convey a cold light, on a black background inside

which the “Deposition” is placed on four marble

stairs, within a simple structure of metallic tubes.

The second one is more articulated, with a richer

shooting technology made up of more cameras, a

background panel representing the turbulence of

a stormy sky cut by a ray of light falling onto the

“Deposition” and onto the cross on the central

pedestal, at the bottom of which a second group

of people in semidarkness is present, emphasising

the dramatic character of the event.

Between the two works there is a decade in which

Gerico realizes a huge “Live Museum”, going though the beauty, the dramatic character and the stage complexity of this unquestionably ingenious painting.

Research implies a concrete risk.

When a successful result is finally found, there may be the obvious risk of stranding in it, turning it into a final solution.What is obtained becomes a rewarding and easily repeatable formula.

Yet, this is an attitude which a real researcher refuses by nature, and because his research is

nothing but a philosophical journey within a continuous and wearing challenge with oneself.

The result is therefore a stage, an important moment for which it is worth stopping for a while to start walking again, leaving back what has been made with the meaning of an acquired positive experience.

So, the “Live Museum” period also comes to a logical conclusion. Once all survey opportunities are over within this contamination of the different ways to stage a work of art, Gerico stops.

A further result has been achieved and the author is not interested in a further repetition of it, as he is already looking for new creative stimuli.

Contemporarily to this research, already in 1983 Gerico dedicates himself passionately to the portrait, he does it with the same attitude as the masters of the XVI century he pays homage to.

The client wants to be depicted in a certain way and in a specific context: these requests represent an important stimulus with two objectives: to reward the person immortalized and to satisfy the creative needs of the author, which imply an adequate constructive implant and eloquent psychological implications in the identity of the person immortalized.

................................(16) ................................(16) |

appear evident, like the suggestive “sailing” collocation of “Maurizio” (1988-fig.14), the refined elegance of “Edy Guerrini” (1989-fig.15),

the passionate identication of “Leda” from

the “Ovid’s Metamorphoses”, performed by mrs

“Paola”. (2007 -fig.16)

Always in 1983, a new research reason starts, the

one later dened as “Natura in Posa” (Posing

Nature).

“The theatricalism of staging - explains Gerico

- has led me to consider the big theme of still life. Fruits and vegetables have been the same

for centuries, but for me they are not normal still life, because there is this strong link to the theatricalism which stimulates me to stage fruit in order to show it in all its beauty and arrogance”.(Fig.17).

We may speak about a research in the unnaturalness of nature: it is just like when we state

something is so beautiful it looks fake or so fake to look true. In this ambiguity between fiction and reality, once again the “staging” becomes illuminating for the contents proposed with a wise and rigorous painting.

What should not be forgotten, moreover, is that the author uses acrylic colours with a personal technique able to make them warm and mellow as if they were oil.

The expressive violence of a savoy (fig.18), the arrogance of an apple or the presumptuous beauty of a fig leaf do not wink at a hyperrealistic construction, but they fill the painting with a

new theatricalism, supported and highlighted by some outside elements introduced intentionally.

Warmth and coldness melt together, recreating images calculated in their balance, also thanks

to an entrapment realised by tightened threads meeting in the painting to define spaces and luminous refiections.

................................(18) ................................(18) |

Stage suggestions in an unreal environment, in

which light dialogues with anything beingexposed: in short, this is the visual sensation which characterizes this further theatricalism of the image made by Gerico.

In a “click” we can summarize the great pictorial challenge that Gerico decides to consider starting from 1999, when he starts a long journey in Dante’s literature.

It is a path which maintains its own personal autonomy and which he faces together with three other painters: Edi Brancolini, Danilo Fusi and Impero Figiani, the former from Modena and the latter two from Tuscany.

They all share the desire to find expressive forms which through painting are able -without any foolish illustrative aspiration- to confront themselves in the interpretation of a literary text which

represents one of the highest in the history of literature: the Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri.

Once again, just like in the approach to the “man-machine” relationship of the early ‘70s, the author identifies beforehand a choice of contents which are different from the cultural interests

of that time.

It is a “click” which symbolically contains this complex and original route.

The click of the digital camera: the speed of an instant in order to obtain a result which is immediately concluded in millions of pixels, the noise made by a fingertip onto the “enter” button of the pc keyboard.

A contemporary mix, in order to use the most advanced technologies in the best way in function

of a classical and universal thought.

“Ultimate navigation” is the title given to this operation, shared by Gerico with his travel-mates

and witnessed not only though the works and studies made, but also through a travelling didactic exhibition recording over 30’000 visitors and supported by an important catalogue edited by Giorgio Segato (publisher La Litografica, Carpi, 2000).

The subtitle of the catalogue states: “Four visual routes within Dante’s man”.

(These “convergent” routes are not the result of improvisation; in fact, Gerico’s painting is everything but improvised and superficial. Already in 1997, the same publisher releases the catalogue “4 painters with a crystalline view” edited by Giorgio di Genova, cementing the artistic brotherhood between Brancolini, Fusi, Gerico and Nigiani, who share a common idea of pictorial language and fully live modernity respecting tradition).

“In this work of mine around the single episode - comments Gerico - I develop a representation

which links all works in a single reading code”.

Gerico has always been particularly attentive to confronting the growing real cosmos: being the

pc a daily element of contemporaneity, it can’t but appear in his pictorial narration, but in this

case the machine also represents the knowledge of the great poet, able to reconstruct in this work all his knowledge of an era, never detached from the satisfying learning of the classics.

“I always start from a colourless black space just like internet, which does not give any colour idea - adds Gerico - and this idea may be a symbol of the cosmos, of everything and nothing, in a dust inside which everything and nothing live together.

This dust, from which everything starts, is the collective space-time memory of humankind. Every dot, no matter how minute it is, contains an eternally fiuctuating story.

With the same operational dynamic as the pc and the specific verses of some Dantean tercets, I detect one of these minute dots and I transport it onto the foreground, so that it may offer a detailed visibility to the considered circumstance”.

Let’s take, for example, a sensational episode and let’s try to tell it to understand the mechanism of the representative technique.

“Paolo and Francesca”, acrylic on linen canvas, 80 cm x 100 cm (1999) fig. 19: the starting

idea is a sort of connection with the “Dantean site”, identiable in a cosmos studded with many dots. The surfing on Internet starts from the foreground, where a computer keyboard is present, which can be symbolically used to link to one of the multitudes of tiny dots in the top part of the painting.

The contact is visualized in a light cone starting from that distant universe with a series of bigger and bigger concentric circles, the last of which focuses in the middle of the work the episode analysed.

If we “zoom” on Paolo and Francesca, embracing one another, they are two bodyless souls, two mysterious figures without an identity, dramatically attracted to one another and slightly

placed on the big book, which represents the alibi of their scandal of love.

Behind their back, the grey sensuality expressed by bodies in fatuous steams reminds of the lustful sins.

On their right part stands Dante, coldly dressed up in the same colourless mantle.

In their meetingthere are also five tercets from the V Canto of Hell, literal witnesses of one of the most known and intense dialogues of the whole Comedy.

In front of this totally comprising darkness, placed on the keyboard opposite the starry sky, Gerico sets a ruddy and sumptuous apple in all its arrogance, result of that sin as well as real and invading element able to transmit an estranging warmth in the gloomy and cold complexity of the painting.

This type of analysis concerns an immediate and artificial approach which cant be easily translated in words, as Gerico’s work deserves a deeper attention in the game of visual possibilities and in the construction of iconographic symbols.

In the light of this original and precious experience of “navigation” within the Dantean

Comedy, comprising new didactic values in the relationship between the literary text and the

iconography always accompanying it, the representation route of Dante’s work goes further. Corrado Gizzi, director of Dante’s House in Abruzzo, author of many important cultural initiatives aimed at keeping the figure of the Great Poet constant and bright, proposes the four artists (Brancolini, Fusi, Gerico and Nigiani) a challenge none has ever faced so far: the pictorial interpretation of “Vita Nuova”.

“The invitation to carry on with this wonderful journey -tells Gerico- has certainly been a further research stimulus. However, in this case, the iconography available was very little, almost nonexistent, and when you read the work you realize why nobody has ever tried to interpret it in images”.

In Autumn 2003, after a lot of hard work and enthusiasm, the Caste Torre de’ Passeri in Pescara houses the volume and the exhibition dedicated to “Vita Nuova” interpreted by the four artists.

Gerico maintains the structural layout of the previous paintings, still identifying a strong emotional component in the representation weaving: a background of dark and stormy clouds from which a central theme emerges contained in a synthesis of simplified geometries and a foreground on whose basis, instead of the computer keyboard, there are: an open book on uncut pages, an inkpot with ink and pen scanning time and the ballet of a dancer, direct interpreter of the words and thoughts dedicated by Dante to an angel-like Beatrice

(Beatrice’s death, cm 80x90, fig.20).

.............................(20) .............................(20) |

This project hasn’t got any precedent too, so, once again, a methodical and in-depth study of

the texts is required to produce an original and pertinent creativity.

Gerico, for this project, looks for a new reading key, to go beyond the solutions adopted in the

previous interpretations of Dante, yet confirming the same graphic layout.

“By keeping the concept of a collective space-time memory - comments Gerico - in this dimension I have created two openings, two circular perspectival cuts in which there is a column that becomes a dug theatre where sculptural shapes come to life from the marble itself in a sort of reality springing from myth”.

................................(21) ................................(21) |

In this framework, particularly symbolic are the mythical figures of “Aracne”, (2006-cm 80x80-fig.21) with her eight twisted limbs in the harmonious femininity of her body, and of Leda (2006-80x100- fig.22), whose sensuality composes itself “under the swan’s wings” quoting a passage from Ovid’s Metamorphoses and contemporarily the 97th and 98th verses of the XXVII Canto of Paradise: “The virtue that her look endowed me with? From the

fair nest of Leda tore me forth,?And up into the swiftest heaven impelled me”.

|

It is not easy to characterize the figure and the work of Gerico, also because he is not an author that can be referred to a definition of a univocal scheme.

His curiosity and his intentions have always taken him in front of a reality rich in human drama in a fragile cultural becoming and in biting questions; his sensitivity and his thought have projected him along paths plotted in the immense fiuctuating universe of research.

This research offers the man and the artist the opportunity to deeply perceive the joys and sorrows of his essence, characterizing them in a personal cosmos of images.

“This characterization - rightly states Gerico, never limits the renewal impulse because, although no sailor, while sailing, has ever reduced the distance from the horizon, sailing remains an ungovernable vocation, and gaining more horizons is the most desperately vital emotion for every human being”.*

Crema, February 2008

Fausto Lazzari

(14)

(14)